Allison Krause Believed "Flowers Were Better Than Bullets." Kent State Proved Otherwise

The lessons of the Kent State shooting still haunts America.

Grim Reminder: A Grim Historian is a reader-supported newsletter and depends on your 5$ donations to keep the most depressing politics and history in your inbox. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber or share with someone who loves misery.

It was May 4, 1970, and Kent State smelled like burnt coffee and fresh-cut grass. The ghost of yesterday's tear gas still clung to the breeze. The Commons, a student gathering place for last-minute cramming, was filled with chatty teens and frisbee games.

These students weren't radicals. Many of them had voted for Richard Nixon. He had promised to end the war. Instead, he escalated it in Cambodia.

Still, most students couldn't identify Cambodia on a map. The internet didn't exist, TVs were not in dorm rooms, and the radio had little news that interested college students. But they knew that their friends were getting drafted, and they knew their friends were dying.

The protests started small, almost lazy. There were a few signs, some scattered chants, and a bonfire where a couple of kids torched draft cards, more as a joke than a rebellion. At first, it felt like any other college spectacle—more Woodstock than a war zone. Bands played, and people laughed. But something shifted as the weekend went on.

Two days earlier, the governor of Ohio, James Rhodes, compared the protesters to Nazis "worse than the brown shirt and the communist element." He sent in the National Guard — young men barely older than the ones they faced, gripping rifles like lifelines.

On the morning of May 4, parents sent their children back to campus, reassured by the presence of the National Guard.

Soldiers were supposed to make a college campus safer.

The students didn't think they were in danger either. Not really. They hollered chants of "Pigs Off Campus and No More War!" Some students threw rocks. Some, like Allison Krause, handed them flowers.

"Flowers are better than bullets," she said, watching a young guardsman accept one and place it inside his gun, his rifle no less menacing with a daisy in its barrel.

No one thought the guns were loaded. No one thought they would fire.

By noon on May 4th, the mood had soured. The students were angry, and the National Guard was tired. Someone set fire to the ROTC building, and firefighters arrived to put it out. They were met with jeers, then more rocks. They threw teargas at the students, only for the students to pick up the canisters and throw them right back.

The guardsmen became fearful and shifted back up the hill. Then, they turned and raised their rifles in perfect unison. Bayonets flashed in the afternoon sun.

First came the pop — a crack, like fireworks at a cheap county fair. Then another. And another.

Thirteen seconds. Sixty-seven bullets.

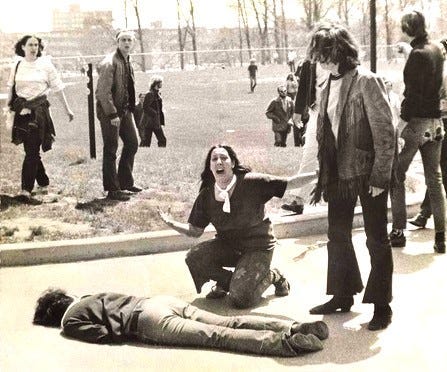

Jeffrey Miller hit the ground first. His blood pooled beneath him, dark and spreading. John Filo, a student photographer at the time, snapped the moment just as fourteen-year-old Mary Ann Vecchio fell to her knees beside his body, her scream frozen in history.

This one grisly photo would become the Vietnam War's open casket.

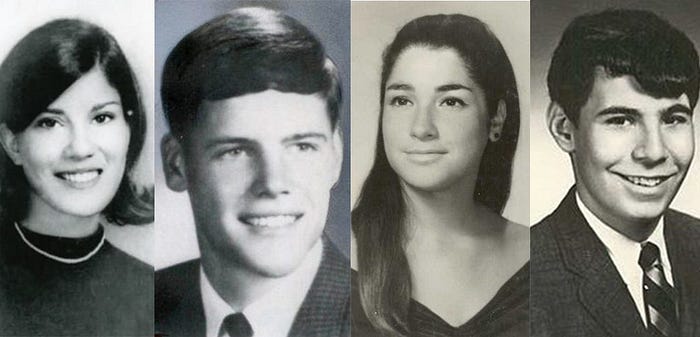

Allison Krause lay nearby, her belief in flowers over bullets stamped out in the dirt. William Schroeder had been walking to class when a bullet tore through him. Sandy Scheuer, who hadn't even been protesting, took a shot to the neck. She died shortly after.

The National Guard left the field in silence. The students were still screaming. Nine were injured. Four were dead.

Then came the aftermath.

Blame was swift and vicious. Not on the guardsmen who fired, but on the students who died.

"They should have shot them all," one student witness recalled her father saying. It stung. She could have been one of them.

Another Kent State student recalled, "I was shocked to learn that some people thought that the National Guard should have shot more students and that some of the families of the wounded blamed their own children. I still have a hard time trying to put that into a perspective I can understand."

Governor Rhodes shut down the university. Nixon called the protesters "bums." A commission labeled the shooting "unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable." But nothing happened. No charges. No accountability. The men who pulled the triggers melted back into civilian life.

But something changed in the hearts of Americans. This massacre didn't happen in Saigon. It happened in Ohio. The war was no longer a distant nightmare playing out on evening news broadcasts. It was here, spilling American blood on American soil.

And for what?

Within days, campuses across the nation erupted — not with bullets, but with bodies. Hundreds of thousands of students walked out. Professors shut down classes. Parents who once muttered about "damn hippies" suddenly saw their own children in the fallen.

Public support for the war nosedived.

Four million Americans took to the streets. And for the first time, the anti-war movement wasn't just the counterculture — it was the culture.

Kent State had proven something ugly. The government was willing to shoot its own children to keep them in line.

Flash forward to today, and Trump has threatened to imprison student protesters and cut funding to any college that allows students to exercise their First Amendment rights.

Guess what happens when you tell young people not to do something?

That's where the next chapter begins.

"It could have been me."

In the aftermath of Kent State, the phrase "Four Dead in Ohio" became a rallying cry, immortalized in Neil Young's protest song. It was an indictment, a demand for accountability, a refusal to let the moment fade into history's long archive of forgotten tragedies.

If you read through the eyewitness accounts of the Kent State shootings, one statement is repeated over and over again by the student who survived that tragic day — "It could have been me."

The Kent State shooting was the moment when Americans could no longer ignore the cost of their government's decisions. It forced a reckoning, not just with the war but with the unchecked use of force against civilians.

Empathy — the very thing Musk dismisses as a "fundamental weakness of Western civilization" — is what turns personal tragedy into collective action. It is what compels people to march, to vote, to demand better.

It is what keeps names like Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause from fading into history.

In the end, Kent State's lesson is not just about the past—it's about whether we are willing to see ourselves in today's struggles. It’s about whether we recognize that silence is complicity and whether we believe, as those students did, that a different world is worth fighting for.

It's the moment we acknowledge— It could have been me. It could have been anyone.

Allison Krause believed flowers were better than bullets. But flowers didn't stop the bullets. And when the next generation of students rises up — and they will — the question is whether we've learned anything at all.

Carlyn Beccia is an award-winning author and illustrator of 13 books. Subscribe to Conversations with Carlyn for free content every Wednesday, or become a paid subscriber to get the juicy stuff on Sundays.

This brought me to tears. Thank you for writing it.

I am a native Ohioan. Some of my relatives, now deceased, would have been MAGA in today’s world. During a family gathering at my aunt’s house the subject of Kent State came up, not long after it happened.

An adult cousin, an otherwise nice guy named Sam ( college graduate, professional, President of a construction company), literally exploded.

He started yelling that the students were swinging tire chains and they deserved what happened to them. We were stunned. Sam was enraged. I remember two of my Aunts shaking and staring into space. I’m glad my Mom wasn’t there, because she would have probably have been mortified. My Mother could be a firebrand and when confronted with BS like that she could literally explode.

Anyway my cousin Rick and I went downstairs to the den and had a shot of single malt. Rick kept shaking his head and looked deathly pale. What a day. Kent State was a disgrace to our country. That’s the kind of polarization that exists today.